Naming, Renaming, and Inventing

Mostly Edge Cases

Last time, in “What’s in a Rename?”, I called “Jhanabros” and “Doomers” renames. Before that, in “Making A New Type of Guy to Get Mad At”, I had called them inventions.

So—what gives? Am I confused?

Or is this just… hard?

Classification is Hard, so let’s start with easy ones

I want to distinguish between three ways of classifying new words: Naming, Renaming, and Inventing. Analytically, here’s how to tell them apart:

Naming → A pattern exists. Later, a new name is created for it.

Renaming → A pattern exists, already named. Later, it is given a new name.

Inventing → A new name is created for no pattern in particular. The name might promote a pattern coming into existence or can get reappropriated for an existing pattern.

Let’s go through examples of each of these.

Naming

This is the simplest case. Something exists, and it’s given a new name: ”tree”, “red”, “thunder”. Most names are of this kind.

Renaming

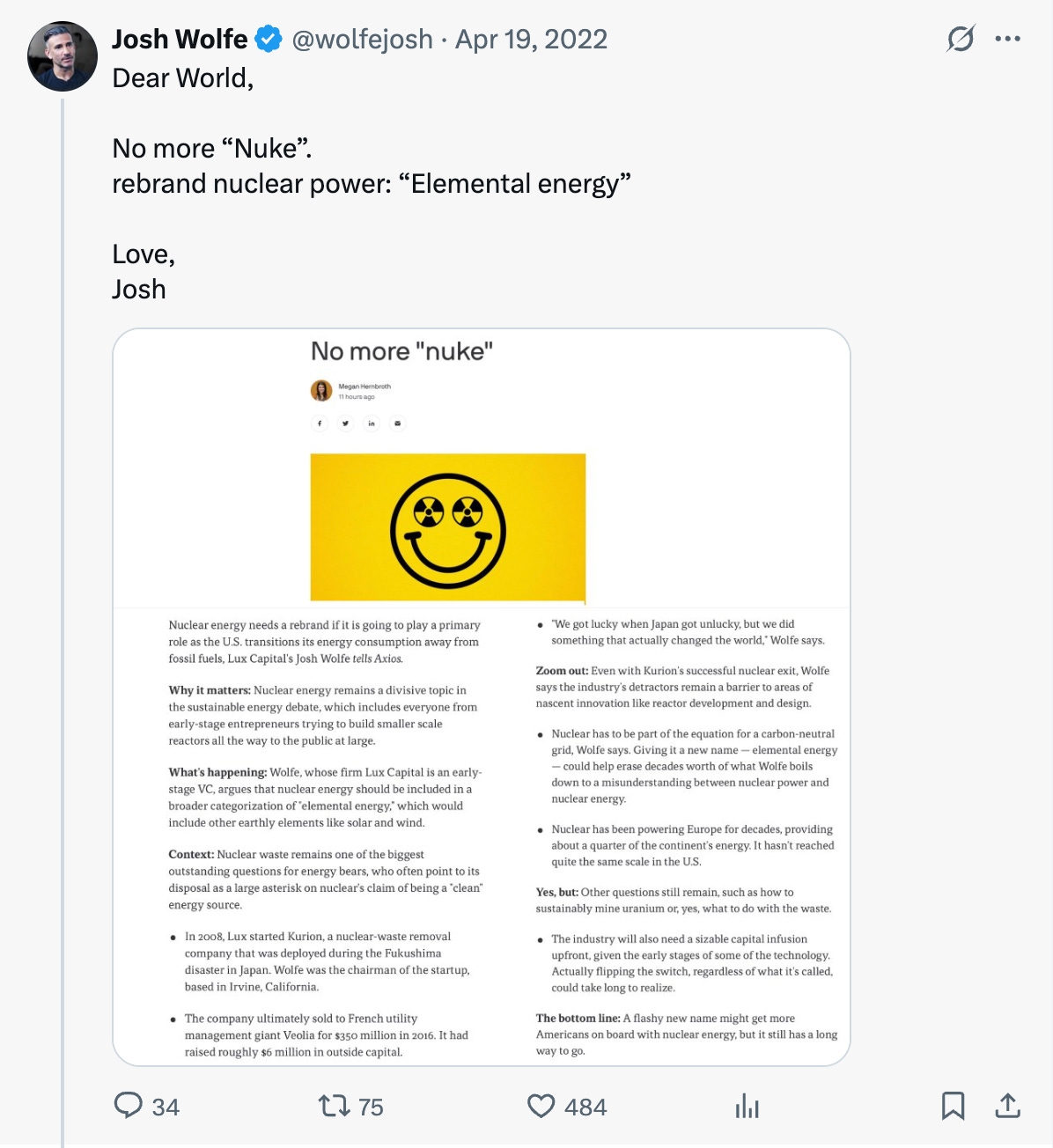

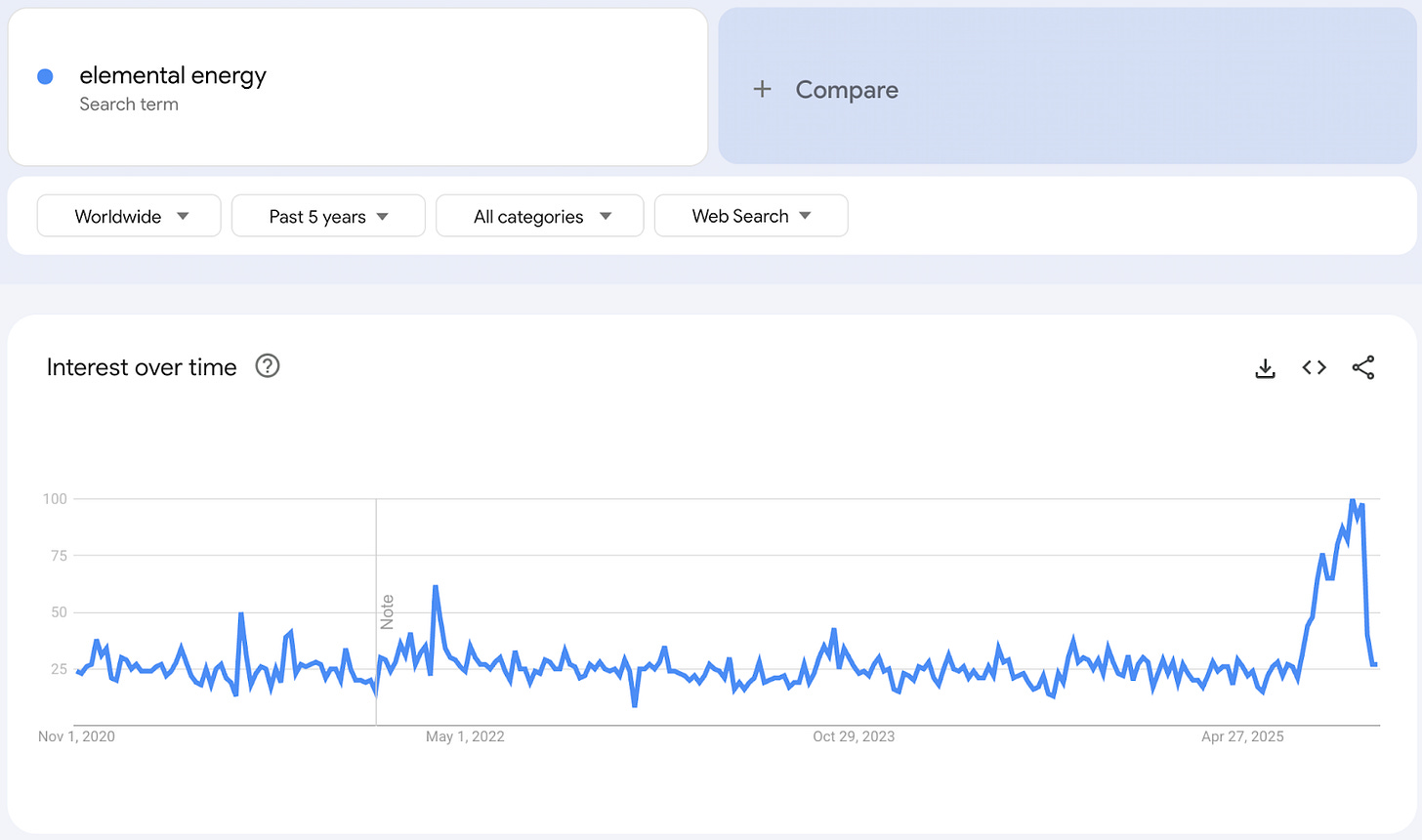

Something exists, already has a name, and is given a new name. Renaming is easier to see when it fails, just as the mechanics of things become more obvious when they break.

A failed attempt at renaming.

Inventing

The word “Bitcoin” was invented to describe… Bitcoin. The word and the thing it described co-emerged.

“Chortle”—now meaning “to laugh in a breathy, gleeful way; to chuckle”—first appeared in the nonsense poem “Jabberwocky” as a meaningless word, and only later acquired the modern meaning.

So far, so easy. Let’s make it harder.

Hard

1980s. Western-trained psychiatrist Dr. Sing Lee was practicing in Hong Kong when he noticed something odd: cases of self-starvation existed locally, but none resembled Western-style anorexia nervosa i.e. no obsession with thinness, no fear of fatness, and no dieting culture.

Then, in 1994, a teenage girl named Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying collapsed on a busy street and publicly described her condition using the Western label anorexia. The story spread through Hong Kong’s media and, within months, Lee began recording a surge of new cases that perfectly fit the Western template: young women refusing food out of fear of gaining weight.

From 1983 to 1987, Lee had seen only two or three cases per year of self-starvation, none involving fat-phobia. After 1994, both the numbers and the symptoms changed rapidly: fat-phobic, Western-style anorexia nervosa became the dominant presentation. ([source])

Lee’s conclusion was that the word itself, and the cultural narrative it carried, had conjured the disorder into existence where before it hadn’t existed.

Perhaps you agree with Lee — “Anorexia didn’t exist before 1994 in Hong Kong.”

Perhaps you don’t — “Anorexia did exist; they just didn’t call it that.”

The point is: it’s hard to say. Not only is it hard to say but it matters.

If the disorder already existed, naming was useful: it let doctors import existing Western medical knowledge.

If it didn’t, the spread of the name was catastrophic, effectively generating a new illness almost ex nihilo. A case where naming itself became a public-health threat, suggesting we might need to carefully control which diagnostic labels spread, an idea that cuts against the purported Western commitment to information freedom

The point is this: for any one word we might plausibly care about, it is more likely than not to be a difficult to classify edge case because classification isn’t neutral—it implies an ontological claim: are you “merely” describe something that already exists, or are you renaming it in a more positive or more negative way, or even trying to bring it into existence through the act of naming it?

This territory—of naming, renaming, and inventing—is ambiguous and this ambiguity not only matters but can be actively exploited.

But that’s for another essay.