Semantic Arbitrage

Picture theory and what it enables

Yesterday we ended with the thought that the Augustinian/Folk theory of language is mistaken in ways that open the door to various exploits. Today we look at some of those, each organised by the specific mistake it depends on.

First, recall how Wittgenstein characterised the Augustinian picture of language:

Words name objects.

Sentences are combinations of names.

The meaning of a word is the object it stands for.

Learning language = learning which names attach to which things.

From this picture, several structural assumptions follow. It is those assumptions that enable the four types of mistakes below.

Picture Theory Mistakes

Mistake #1 — Naming = Reality

The Augustinian assumption:

A word names an object; the name reflects its essence.

If names reflect essences, then a softer name means a softer thing, a sacred name a sacred thing, and an authoritative name real authority. This is exploited by creating or subbing in names that make people feel differently about what’s named.

E.g.:

“Collateral damage” ← dead civilians

“Enhanced interrogation” ← torture

“Baby” ← foetus

“Mostly peaceful protest” ← riot

“Fascists,” “Racists,” “Denialists,” “Science-deniers” ← people on the opposing side

“Experts,” “Scientific,” “Pro-science” ← people on our side

Mistake #2 — Definition = Meaning

The Augustinian assumption:

Words have fixed meanings; meanings live in definitions.

If meaning just is the thing named, and the definition captures its essence, then to know the definition is to know the thing itself. This mistake is exploited by changing definitions as if that changed the underlying reality.

E.g.:

“Patriot” → supports our policy agenda

“Science” → institutional consensus

“Harm” → anything we dislike

“Terrorism” → violence by people we disapprove of

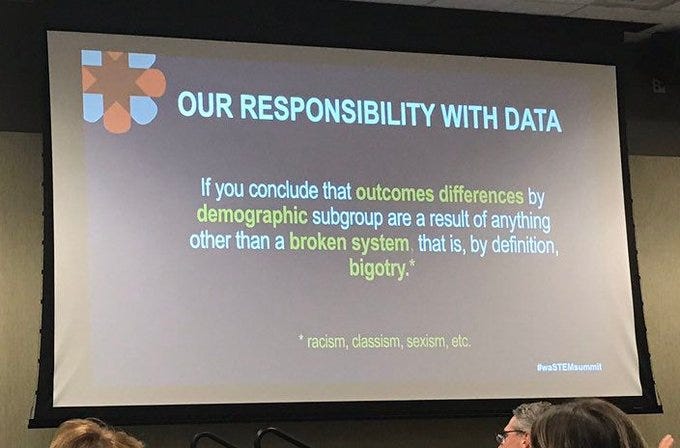

A particularly egregious example

Mistake #3 — Use = Mention

The Augustinian assumption:

Using a word is applying the name of the thing.

If using a word is “correctly naming the object,” then the essence of a thing is encoded in its name. The exploit here is to get you to use a label that bakes in a judgement so it doesn’t have to be argued for.

E.g.:

“Pro-life” cannot but be life-affirming

“Microaggressions” cannot but be aggressions

Opposing “Hate speech” cannot but be hateful

“Trans women are women” cannot but be a tautology

“Love is love” cannot but be a tautology

“OpenAI” cannot but be open

Mistake #4 — Categories = Essences

The Augustinian assumption:

Words carve nature at its joints; categories correspond to real essences.

If categories are treated as natural kinds, then shifting their boundary looks more like discovering the truth than redefining a term. This is exploited by getting you to accept a new boundary, because shifting who counts as X smuggles in a new conclusion about what X “really is.”

Examples:

“You ain’t Black if you don’t vote Dem” excludes political opponents from the ethnic category

“Real America” excludes urban/coastal areas

“True patriots” excludes dissenters

“Journalist” is boundary warfare between credentialed reporters and independent/citizen media

“Scientist” excludes heterodox researchers from category

“Terrorist” vs “freedom fighter” name the same acts but political alignment ensures different categorisation

“Hate speech” vs “controversial opinion” — same

These four mistakes share something: they’re invisible to people who hold them. If you still believe the picture theory, you can’t see these as mistakes: they’re just how language works. But if you do see them, like the people who crafted the examples above? Then you can extract value from everyone else.

Arbitrage

You think this wouldn’t fool anyone. You’d be shocked.

In financial markets, arbitrage means spotting price asymmetries and profiting from the gap. The same pattern applies here: there’s a gap between what people think language does and what it actually does.

That gap creates the four mistakes—or, attack surfaces—above. When someone exploits these gaps, they’re doing semantic arbitrage: extracting political or social value from the mismatch between folk theory and reality.

When this becomes systematic, that is, when actors coordinate around these exploits, or actively manufacture the confusion they’re profiting from, you’re no longer looking at isolated instances of manipulation.

You’re looking at war.