Why we fight

Series Conclusion

Intro

I am PISSED OFF that it took me reaching the end of this series to realize what I’ve been trying to say all along.

Perhaps I’m just human, all too human—maybe only by muddling through does the through-line become evident.

Then again algos seemingly do the same.

Anyways, with my whining out of the way, let’s review this series:

What have I been trying to say this whole time?

The Thesis

Linguistic conflict is structurally inevitable in modern life.

The reason is that words don’t merely describe social reality, but construct it. Said differently: in social domains, language is reflexive. However, nearly everyone operates under a false folk theory of language that denies this.

And this shared false theory does double duty:

It holds social reality together (someone says something → people act as if it were true → in doing so they make it true)

It also enables attempts to reshape it through linguistic attacks.

Because social reality is downstream of what people collectively believe, and language changes what people believe… controlling language becomes a way of controlling reality.

The false folk theory of language is, at its core, a philosophical model. People don’t misunderstand grammar; they misunderstand what words are and what they do: they think that names attach to essences / categories reflect natural kinds / definitions fix reality / meaning is a picture in the head.

Those are metaphysical and epistemic—i.e. philosophical—errors. They have linguistic consequences, sure. But they’re not linguistic errors. That is just how they manifest.

The entire series has been about how these shared philosophical mistakes are the terrain that allows persuasion aimed at shaping social reality to unfold through conceptual conflict.

Methodology

Awesome. With that out of the way, some self-critique: I worry about this series. Specifically about the examples used. Two reasons.

One is that they overwhelmingly come from the Internet. People might justifiably think this whole thing has been just “Twitter inside baseball”. I’d like to push back on that.

Fact is that the Internet is the perfect laboratory for studying these dynamics because it’s such a high-velocity environment for everything, including language.

It’s online that language evolves the fastest, which makes its evolution happen at observable speeds: slang, memes, political labels, identity terms, moral categories—all evolve at the speed of light.

There’s even a meme (’slang overload’) for this phenomenon for goodness’ sake.

It’s a bit like studying fruit flies except for linguistic evolution: short cycles make for visible patterns.

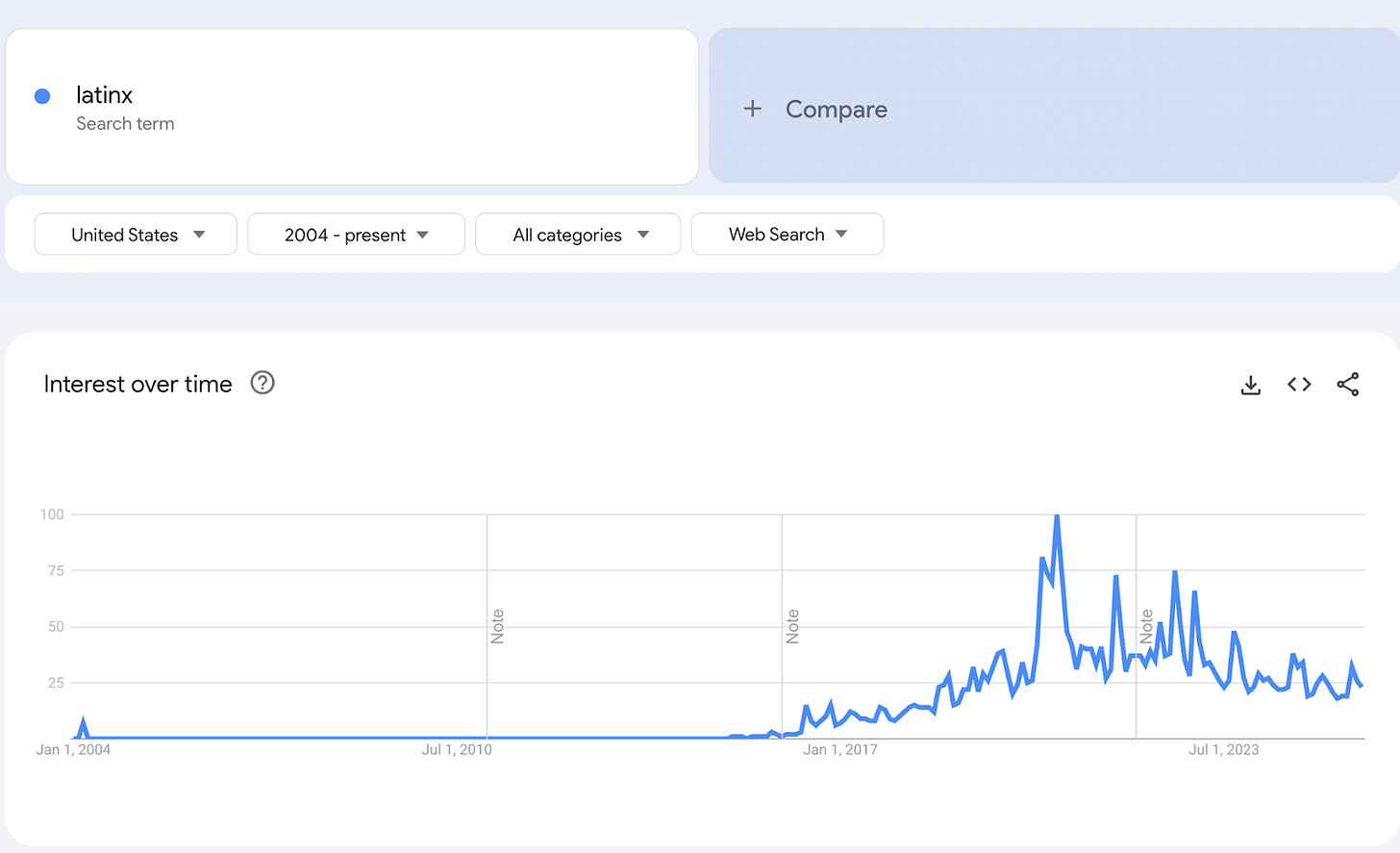

Compare, say, “Latinx”—first proposed in 2004, when we were online but not as online—to “Brat”—twenty years later. “Latinx” took 15 years to go from proposal to peak adoption around 2019 and then three more years to reach widespread rejection in 2022. A nearly two decade cycle. “Brat” went from Charli XCX album aesthetic to being adopted by Kamala Harris’ campaign to saturation, becoming “cringe” and dying, in about 3 months. Being more online has made the cycle faster and online is where it’s fastest and, thus, easiest to observe.

Latinx

Brat

Which segues into the second reason I worry: language evolves the fastest online because it’s where linguistic competition is fiercest. Competition is fiercest there because the stakes are political. So many of the examples end up being political. But I worry that using those might trigger people and make it too easy for them to dismiss the whole thing as outgroup ramblings. The whole area just is anti-mimetic, littered with deliberately crafted semantic stop signs made to make people look away. It works and I don’t know what to do about that.

The End

All of the above can all be distressing to see clearly: Socrates got killed for destabilizing social reality; Plato coined ‘noble lies’ as his own response and avoided the same fate. Societies have often strained over too much insight into their own working. It’s entirely possible to me that should the ideas in this series become popular they could destabilize the good parts of social reality (Arguably this already happened with post-modernism.) I don’t know which way the calculus leans.

I do know this, though: language is what many people think with, and it’s been so tampered with it has become difficult to think at all. Further, social reality is, first and foremost, constituted by shared thought. That makes me worry for the stability of our social reality as is and I’m confident that, should it falter, proper thinking is necessary for whatever comes next.

So let me say the quiet part out loud, the reason we’re fighting over language so much, the thing this whole series has been circling:

The Map is the Territory.